During palliative sedation, healthcare providers estimate whether the unconscious patient feels comfortable. This is done by clinical observation – checking whether the patient is showing signs of pain. New doctoral research by Dr Stefaan Six at VUB and ULiège now shows that observational estimates of consciousness and pain do not always correspond to neurophysiological indicators. As a result, the patient’s suffering may remain unnoticed or underappreciated. It also shows that monitoring devices can improve clinical assessment. Dr Six: “The study shows that clinical estimates of depth of sedation and possible presence of pain can be improved by the use of monitoring devices during palliative sedation. The study also showed that the use of such monitors was acceptable to all concerned. So we need to think about how we can implement this in healthcare.” The results of the study were published in the scientific journal Pain and Therapy.

The gold standard for detecting pain and discomfort is patient self-reporting. However, in the case of continuous palliative sedation, patients are no longer able to communicate. Several observation scales have also been developed for non-communicative patients, based on inferences from patients’ motor responsiveness. The problem is that these scales equate non-responsiveness with unconsciousness. However, a patient may be conscious and experiencing pain but unable to react.

Although several attempts have been made to improve these observation scales, the main problem in this setting remains unsolved, partly due to the medication used for palliative sedation, which affects motor responsiveness.

The study by Dr Six, a collaboration between the Mental Health and Wellbeing Research Group of the Vrije Universiteit Brussel (promoter Prof Reginald Deschepper, co-supervisor Prof Johan Bilsen) and the COMA Science group of the Université de Liège (promoter Prof Steven Laureys), looked at how the clinical estimates of care providers corresponded with the assessment of two monitoring devices used, among other things, in surgery.

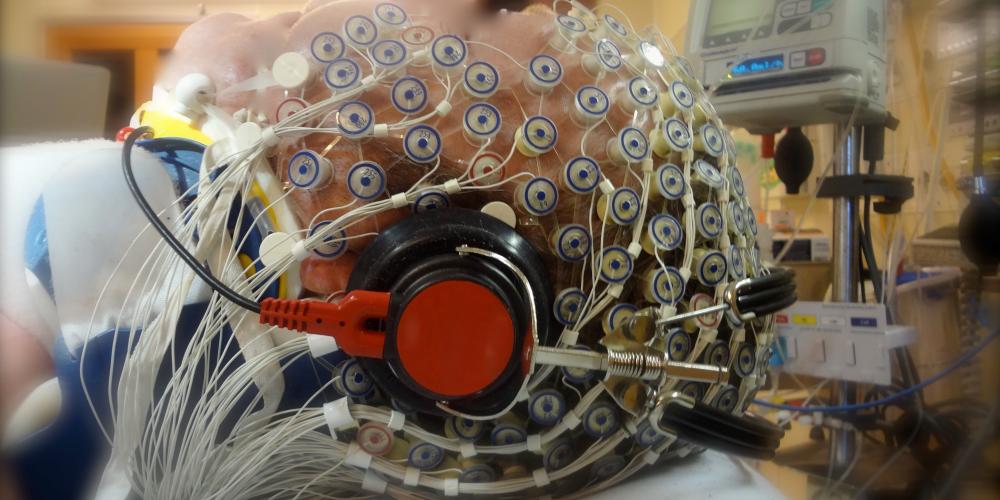

The monitors used were the Neurosense monitor and the Analgesia Nociception Index monitor (ANI). The Neurosense indicates how deeply a person is sedated. The ANI monitor gives an indication of possible pain and can detect a possible overdose of pain medication. A total of 108 assessments were studied in detail in a group of 12 patients. In addition, the researcher also made assessments using four “classic” observation scales.

The results show that there appears to be little agreement between subjective clinical assessments made by healthcare providers and objective assessments made by the monitors. Dr Six: “One of the most striking findings was that if, according to the monitor, there was still possible consciousness, this was recognised by healthcare providers in only 24% of cases and was therefore missed in about three-quarters of cases.”

There also appeared to be little correlation between classic observation scales and monitoring values.

In addition, doctors, nurses and family members of those who participated in the study with the monitors were interviewed. This showed that such objective monitoring was feasible and acceptable to all concerned and its use was considered to provide added value. The findings from these interviews were published this year in the Journal of Pain and Symptom Management.