Three rectors want to increase fees by several hundred euros by 2023. Students respond lukewarmly or not at all. To make the comparison, in 1978, the registration fee was doubled from 5,000 Belgian francs (converted to 123.95 euros then, with inflation now 311 euros) to 10,000 francs. Students across the country then organised continuous protests. Actions ranged from playful trial parties to violent riots. In the VRT series '1985', they took place in, yes, 1985. Together with VUB alumnus Walter Vermander, we look back on these eventful years.

Walter, who are you?

I have been a federal civil servant at FPS Finance almost since my studies, where I work on sustainable development and energy efficiency in the logistics department.

VUB-er?

Yes, definitely. My first year at uni was the protest year 78-79. I started with biology, but that was still a bit much maths and toil in the lab, so I was actually lucky that the students were campaigning throughout the year. Political awareness was very high then. Maybe it was another spillover from May '68? Anyway, among the assistants and profs, there were a lot of people from that protest generation.

What did those protests look like?

Of course, there were the interminable meetings, with endless discussions. There, we collectively decided which action to take. Demonstrations in all university cities and just about everything was occupied that year, all over the country. The rectorates, the ministries, right down to the resto of the VUB. It did not stop. Only by the last examination period did it die down.

I would describe it as a happy, rowdy period. A very different era from today: you had the rise of law and world shops, solidarity movements of all kinds, free radio, and of course the small offset press of Studiekring Vrij Onderzoek. I was the president of the latter, and the printer spit out one political pamphlet after another. Internationally and also domestically, there was the rise of the punk movement, whose political and committed branch appealed to me the most, more than the 'No Future' feeling, which involved only nihilism and no hope of better times. But fair is fair, there was also a lot of darkness in the air. The threat of nuclear war, youth unemployment, the Nivelles gang... these things also contributed to the spirit of the times. And, of course, we cannot forget squatting.

Squatting?

There was a substantial squatting movement near the VUB along Triomflaan. At the time, the VUB had the idea of expanding along that avenue. The university bought up all the houses in the neighbourhood and left them temporarily empty pending construction work. Where the Colruyt is now, there were dilapidated factory buildings and smaller houses. Block one of those squatted buildings housed the so-called wild squatters. Not so much students, but people of all kinds. They demolished the walls in the courtyards to create a big garden together. They had piled bricks on the roofs of back kitchens and outbuildings, as a possible defence against the police.

Fairly idealistic all round, but the garden became a mess and after three months, the block that housed the most notorious rebels was ripe for demolition. The neighbourhood became unlivable, burglars had an extra easy time getting in everywhere through the communal gardens without any trouble.

We were in the second block. You could describe us as 'the braver students'. As such, the squat felt like a small village. It had a communal kitchen and each room had one student in it, with or without a sweetheart. Sometimes a room would become vacant and together we would decide on the new occupant. Temporarily, all kinds of people who needed a place to sleep stayed there. For instance, an elderly hippy from Berlin wandered in who knew a thing or two about central heating. We retrieved an old mazout burner from an industrial boiler and screwed it into our domestic boiler. We were wonderfully warm, and we didn't worry about energy costs in those days. I also remember a Chilean refugee, who came for nights philosophising and drinking our last wine.

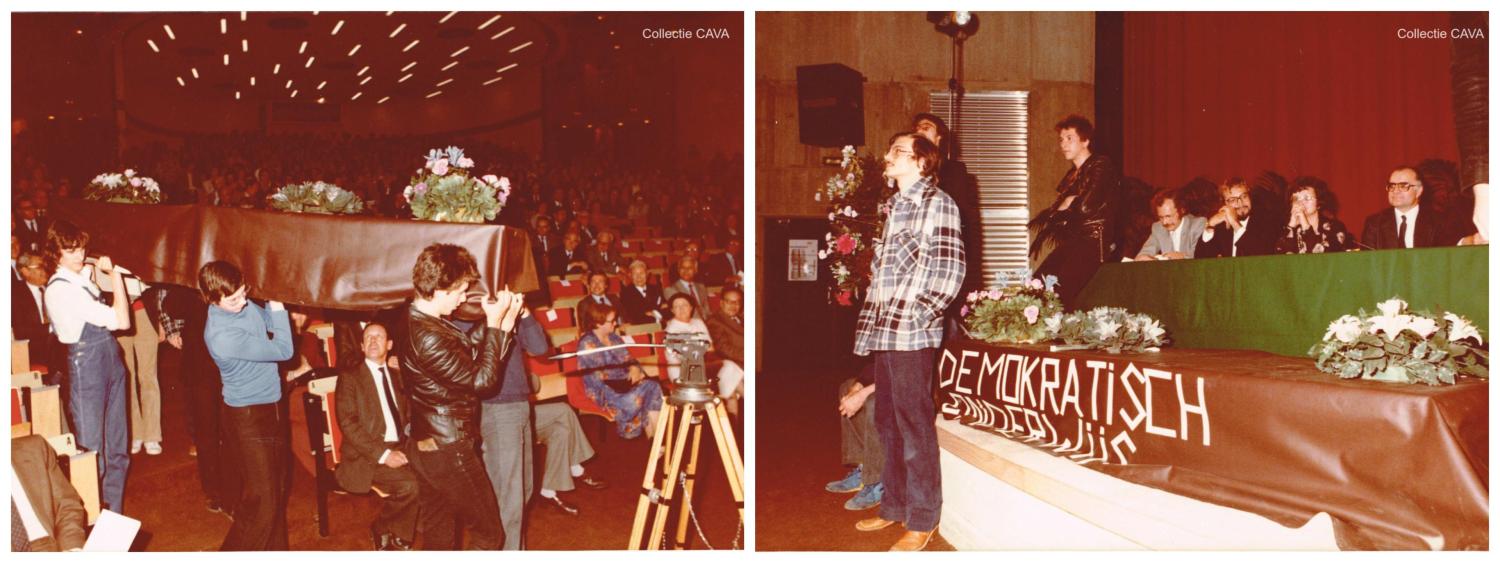

Protest action Funeral of higher education in 1978 (c) CAVA

A breakthrough came after a few years: the VUB recognised the squatters. More than that, anyone registered as a student was allowed to stay in exchange for a small rent. We were even allowed to bring in our expenses incurred for maintenance and repairs. You can already imagine that in the Brico nearby since then, you could never find a leftover receipt!

Did you even have time to finish studies at VUB?

Fortunately, yes. In 1983 I graduated as a political scientist and in 1985 I received my degree in criminology. Proof that you can also be committed and graduate at the same time without a second seat. How did I do that? I maintained good relations with some assistants and was able to use a small room in the 'cigar', now better known as the 'Braem building'. After the Easter holidays, I went there every day from 9am until the night watchman came to kick me out. I wrote voluminous theses there and studied in peace. That was simply not so easy in a squat.

Is there anything else you would like to give to the current generation of students?

I hope students won't let the increase in fees happen. They need to let it be known with a lot of energy that they will not let it walk over them. Let yourselves be heard! But at the same time, I also think students don't need quasi seniors telling them what to do (laughs).