On Wednesday 14 February, British-American historian of science Jan Golinski will give the lecture History of Science in a Changing Climate at the U-Residence on the Main Campus in Etterbeek. In his lecture, he will talk about how contemporary views of climate change are influenced by various cultural and intellectual dimensions. We interviewed him before his arrival at VUB. "People in the ancient world were already aware that human activities could change the environment."

The lecture falls under the VUB's public programme and is part of the KIIP lectures (Knowledge in International Perspective) under the inspiring leadership of knowledge historian and knowledge philosopher Kees-Jan Schilt, professor at the Faculty of Arts and Philosophy. Philosopher, author and curator of the Pauwels Academy of Critical Thinking (PACT) Alicja Gescinska will provide the introduction and join the panel discussions.

Did people once believe that climate disasters were a punishment from God?

“It’s a very long-standing theme of European thinking that disasters are an act of God or a way of God punishing human beings. This is on the one hand widely believed but was also disputed for many centuries. Already in the late 17th century, people are beginning to discount this idea by saying these are all natural occurrences and have nothing to do with divine intervention. But then even in the late 18th century, there are still people who feel they are acts of God. There are different ways these events were interpreted. In the 18th century, they were sometimes called preternatural events instead: not natural, not supernatural but something in between. But these thoughts faded away into the 19th century. So, the religious dimension of this is continuous; I don’t think scientific thinking replaced religious, but it’s interwoven with religious thinking throughout this period.”

How do you look at this as a historian?

“I intend to talk about climate change in terms of what people believed and thought about it. Being a historian, I’m interested in people’s ideas in the past, but also in relation to their thinking about the past, present and future. I’ll talk about the way that in the 18th century, particularly in North America, people thought that the climate was being improved, being made better by human activity. They saw this as part of the general social progress that was being made. Towards the end of the 18th century, there were serious crises and emergencies, both of climatic nature, natural disasters, and human catastrophes like pollution and military conflicts. These events disrupted this previous vision of steady, progressive climatic improvement. Suddenly, people began to worry about the climate that it may be getting worse. As we go into the 19th century, from the 1830s on, the idea becomes that climate is stable and there isn’t going to be any substantial change in the climate, at least not within human history. Climate was potentially regarded as having changed in the deep past, in the geological history of the world.”

Back to the 18th century when people thought about improving the climate. In what way did they think they could make that happen?

“Basically, in the settlement of North America, European settlers believed that they were changing the landscape by introducing agriculture. Which meant that clearing away forest, draining swamps, generally bringing the land under cultivation would make climate better. There were some other things as well, like burning fuels and creating towns on a small scale.”

Have you also studied this belief before that period?

“To some degree. It is actually true that from pretty much before the first European settlements, people were already talking about changing the climate. Even Columbus talked about it, it is a long-term feature of European colonisation of the Americas.”

In what period did science become involved?

“Prevalence of climate as a category for thinking about human relations to the natural world is a sign of a new kind of science, which comes in in the 18th century to try to explain things on a more materialistic basis. Climate does the work of a lot of thinking about human relations to the environment. It is being used to explain why particular diseases occurred, why certain people are healthy and others are not, why certain societies developed and others did not.”

When did humans realise there was a connection between their actions and the climate?

“If you understand climate in rather local terms, people in the ancient world were already aware that human activities could change the environment. Through cutting trees, planting crops, ploughing fields and building houses. Where you choose to have settlements, they were aware that could affect people’s health. The writings ascribed to Hippocrates deal with this. Epidemics were related to what he calls ‘airs, waters and places’. It was also subject to human interference. If you chose the right place to live then you could have healthy people.”

Is there any big lesson we can learn from history?

“The focus of the talk in Brussels is on ways in which we think about climate change in relation to, on one hand, a very long deep history. People now talk about the Anthropocene era, the geological era in which we are supposed to be now, where human activity is substantially reshaping the entire global environment. On the other hand, we think about climate change in relation to events, crises and catastrophes that occur, have occurred and keep occurring more frequently than ever. What interests me is the way we keep in mind those two ways of thinking about climate change simultaneously. We face emergencies and we get perhapredys distracted from this long cosmic view. I don’t have practical suggestions about how to deal with climate change, that’s not my business as a historian. Being optimistic or pessimistic about climate development for me is just a matter of personal temperament, rather than my professional opinion.”

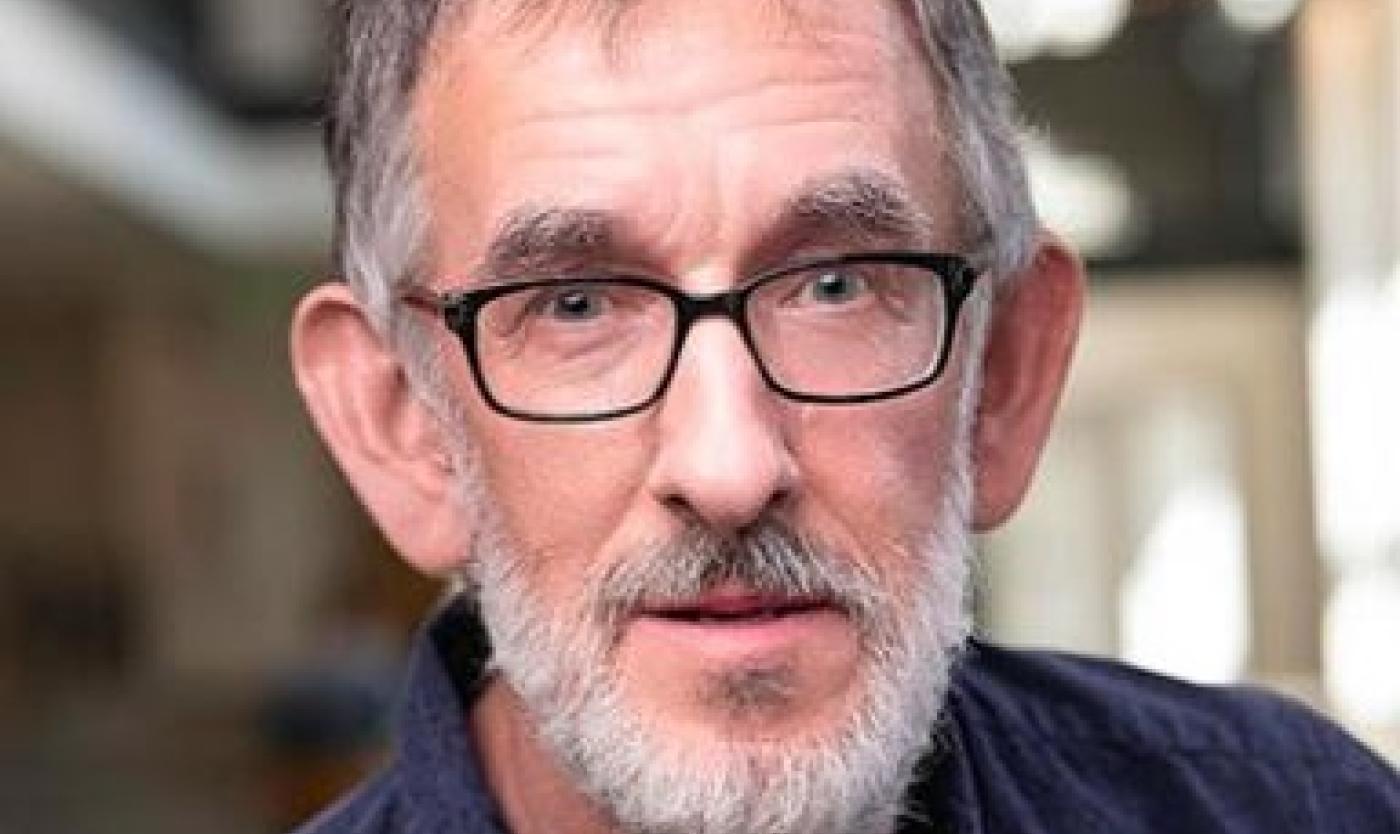

Jan Golinski is a professor in the Department of History and the Humanities Program at the University of New Hampshire. He joined the university in 1990 after a PhD at the University of Leeds in the UK and a postdoctoral fellowship at Churchill College, Cambridge. He teaches courses on the history of science since the Renaissance, European intellectual history and historiography. Professor Golinski’s research focuses on the sciences of the 18th-century Enlightenment. He made his name as the author of several acclaimed books on science in the 18th century. With his book British Weather and the Climate of Enlightenment, he showed that even during the Enlightenment, weather was a subject followed with great interest by scientists and philosophers.