Archaeologists have found the first hard scientific evidence that Vikings crossed the North Sea into Britain in the 9th century with their dogs and horses. Late last century, in a grave from that time in the only known Viking cremation site in the UK, archaeologists from the University of York found the remains of two adults, a child, a horse, a dog and a pig. The remains were subjected to an isotope analysis at the Vrije Universiteit Brussel and Durham University, which showed that at least one adult, the horse, the dog and the pig came from northern Scandinavia. It also showed that the animals were not, as the perception about the Vikings often suggests, stolen from locals along the way.

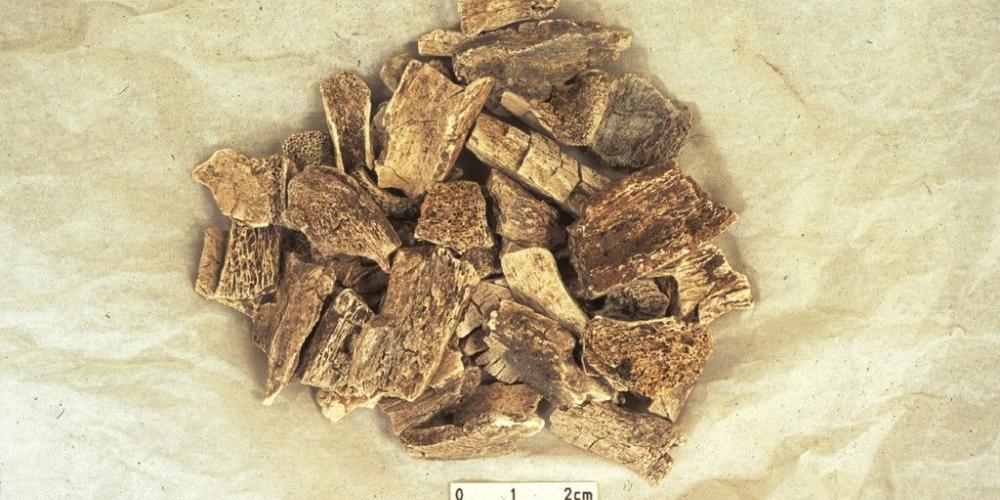

The scientists examined the remains for the presence of strontium isotopes. Strontium is a natural element found all over the world, but in locally different isotope concentrations. The isotope ratio is specific to each site: it reflects the strontium isotopes present in the geological layers. Living creatures absorb strontium isotopes in similar proportions through their diet. When humans and animals eat those plants, strontium replaces the calcium in their bones and teeth. Using the ratio of strontium isotopes, the researchers can determine where humans came from.

“Our analysis showed that one adult and several animals almost certainly came from the Baltic region of Scandinavia, which includes Norway as well as central and northern Sweden,” said lead author of the study Tessi Löffelmann, a doctoral researcher in the Chemistry Department at VUB and the Archaeology Department at Durham University. “The person in question died shortly after arriving in Britain. With carbon-14 dating, we were able to find out that the bones date from the late 9th century, several decades later than the first Viking incursions into Britain. We know from historical sources that a large Viking army crossed the Channel in 865. The analysed remains are associated with that army, a combined force of Scandinavian warriors. The other adult and child may be locals from southern or eastern England. It is possible that they also came from the north, from Denmark or south-west Sweden.”

The research on the remains from Heath Wood, Derbyshire, paints a different picture of the Vikings. Traditionally, they are described in contemporary stories as crude thieves and plunderers. The finding that they brought their own animals to Britain from Scandinavia is new. “Because the human and animal remains were found in the remains of the same funeral pyre, we think the Scandinavian adult was an important person who was able to bring a horse and a dog to Britain,” says Löffelmann. “Moreover, this is the first solid scientific evidence that Scandinavians were almost certainly crossing the North Sea with horses, dogs and possibly other animals as early as the ninth century AD, and this may deepen our knowledge of the great Viking army. After all, the main primary source on this, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles, states that the Vikings took horses from the locals in East Anglia when they first arrived, but that was clearly not the whole story, and they probably transported some animals alongside people on their ships.”

It is possible that the pig was not taken to the British Isles as a live animal. “It could have been an amulet, or part of the food supplies,” Löffelmann says.

“The Bayeux Tapestry shows Norman cavalry disembarking horses from their fleet before the Battle of Hastings,” says Professor Julian Richards of the Department of Archaeology at the University of York, who co-led the excavations. “Nevertheless, this is the first scientific evidence that Viking warriors were transporting horses to England 200 years earlier. Moreover, it shows how much Viking leaders valued their personal horses and that the animals were sacrificed to be buried with their owners.”

The research was funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council (Northern Bridge), the Vrije Universiteit Brussel, the Rosemary Cramp Fund and the Institute of Medieval and Early Modern Studies, both at Durham University.

The research was published in the scientific journal PLOS ONE.