Innovative research at VUB supports transition to circular bio-based society

For decades, we have been extracting materials from natural sources such as fossil fuels without considering the environmental impact. Plastic, concrete and synthetic composites are examples of such materials. But what if we could replace these with truly circular sustainable and biodegradable materials? Elise Elsacker, of the research groups Architectural Engineering and Microbiology at the Vrije Universiteit Brussel, investigated and discovered that fungi offer several possibilities. “With my research, I want to explore the possibilities of new production techniques for architectural applications using fungi. Things like biodegradable temporary constructions, insulation, interior walls and furniture,” says Elsacker.

The traditional manufacturing industry, which is largely based on fossil fuels and raw materials, is increasingly under discussion. On the one hand, there is an abundance of synthetic materials that degrade too slowly (such as plastic), and on the other hand, the agricultural industry generates a lot of biomass waste that is currently burned. Environmental pollution and scarcity of natural resources have led to increased interest in the development of more sustainable materials.

For her doctorate, Elsacker conducted research under the supervision of Prof Lars De Laet and Prof Eveline Peeters into fungi, which can create such circular and biodegradable materials. More specifically, she researched mycelium, the white roots of fungi that form a kind of glue between the fibres. Fungi are omnipresent in natural ecosystems and spend most of their life underground. In the forest, fungi have an essential function: to degrade hard woody plant material. Elsacker studied which factors influence the biological and material properties of mycelial materials, as well as the aspects that play a role in the production of composites grown with mycelium.

Finding the right fungi

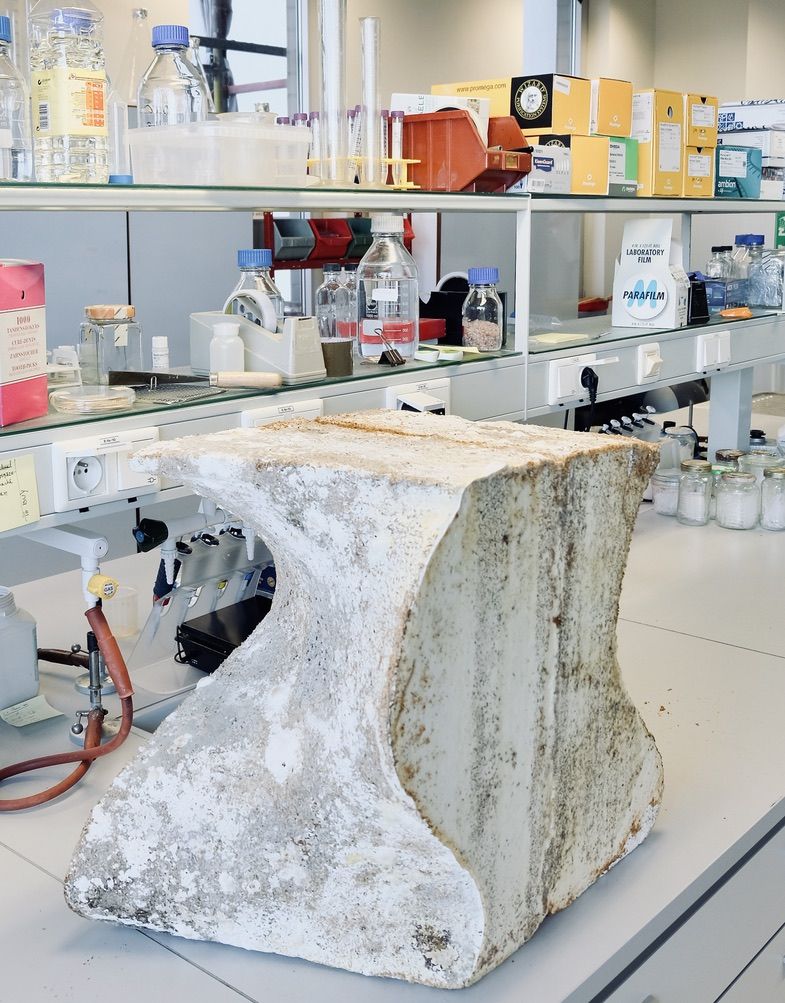

There are millions of species of fungi. Elsacker therefore developed a method to select fungi based on biological, chemical and mechanical performance criteria. She studied the interaction between fungi and fibres and the material properties of these composites with different types of natural fibres, and investigated how to improve their structural properties with various additives as well as by compressing the material into panels. She also developed a new manufacturing process for the production of architectural formwork using robots and experimented with 3D printing mycelium materials, such as chairs made of mycelium.

Will we all be sitting on chairs made from fungi in the future? “Probably not,” says Elsacker. “Mycelium materials are promising, but it is not the intention to replace all synthetic materials with self-growing biomaterials. These biomaterials serve to process waste streams and not to create new waste streams to meet a production demand. The result of my research therefore mainly fits within a strategic transition to a circular, bio-based society. Mycelium materials offer a sustainable answer to the waste of raw materials.”

Elsacker’s research serves as groundwork for further study and new applications: “Fungi can also help us tackle other environmental problems,” she says, “such as growing leather substitutes, sealing cracks in concrete and even remedying pollution from heavy metals and radioactive waste. The fascination with the sophisticated behaviour of mycelium has already extended further at the Vrije Universiteit Brussel with new interdisciplinary research projects.”