This opinion piece appeared in De Standaard on 06/09/2024 – With astonishment, we read the opinion article by historians Dimitri Roden and Antoon Vrints (DS 6/9) regarding, among other things, the work of our non-profit organization Helden van het Verzet (“Heroes of the Resistance”). The tone of the article: for years, resistance fighters during World War II were unjustly treated as criminals. Now, suddenly, they are all considered heroes. Moreover, the article claims there was little resistance in Flanders. So, do not create new myths.

Authors: Dany Neudt and Tim Van Steendam

Discover the VUB Chair “Traces of the Resistance”

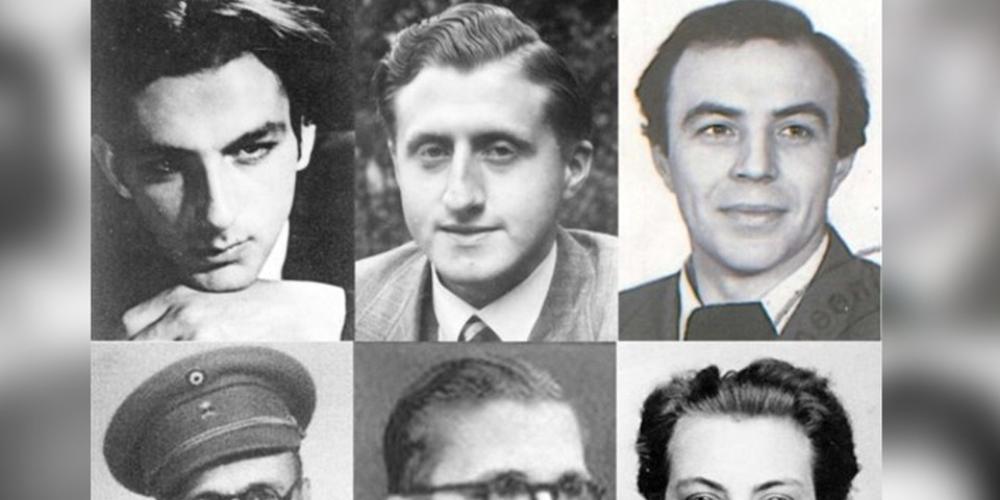

Roden and Vrints cite a series of dry figures and statistics meant to prove that Flanders had fewer resistance fighters than Brussels or Wallonia. Tables indeed show fewer sabotage actions in Flanders compared to Wallonia. But numbers alone prove very little. As experts in Belgian resistance history, they surely know that many Flemish resistance fighters hid in the forested and less densely populated areas of Wallonia. Robert De Preester from Nederename went into hiding in the maquis of Senzeilles before his arrest and execution. 19-year-old Yvan Engels from Ostend died in a firefight in Waterloo. Henri Heffinck, a bicycle maker from Anzegem and one of the most successful secret agents during World War II, carried out hundreds of sabotage actions around Charleroi and Brussels. There are many examples that put the statistics into perspective.

What are these numbers meant to prove? That scientific research into the resistance in Flanders is less important? Colleagues of Roden and Vrints, who in May 2024 established a new Resistance Research Network and are soon publishing a book on the Antwerp resistance, would certainly take issue with that. That we should view the history of the Belgian resistance primarily through a community-based lens? That would catapult decades of scholarly research backward.

Openly minimizing or relativizing the contributions of the resistance is yet another blow to the many survivors and family members of the hundreds of thousands of compatriots who were willing to give their lives in the fight against the Nazi occupiers. We deliberately write “hundreds of thousands” because the true number is unknown. People generally settle on the rounded figure of 150,000 based on the number of recognition dossiers approved after the war. Many resistance members, for various reasons, never applied for official recognition. In other words, it’s an educated guess. Numbers and statistics are rarely a reliable guide in the murky world of war and resistance.

From what point does someone qualify as a resistance fighter? A schoolgirl who smuggled a note in the hem of her dress? A farmer who sheltered a downed American pilot for two days? Or do you only count those who blew up a train or killed a German soldier? How can clandestine acts be defined and quantified—and then used, as Roden and Vrints do, to pass judgment?

“At best, they make us reflect on our own choices in times of danger.”

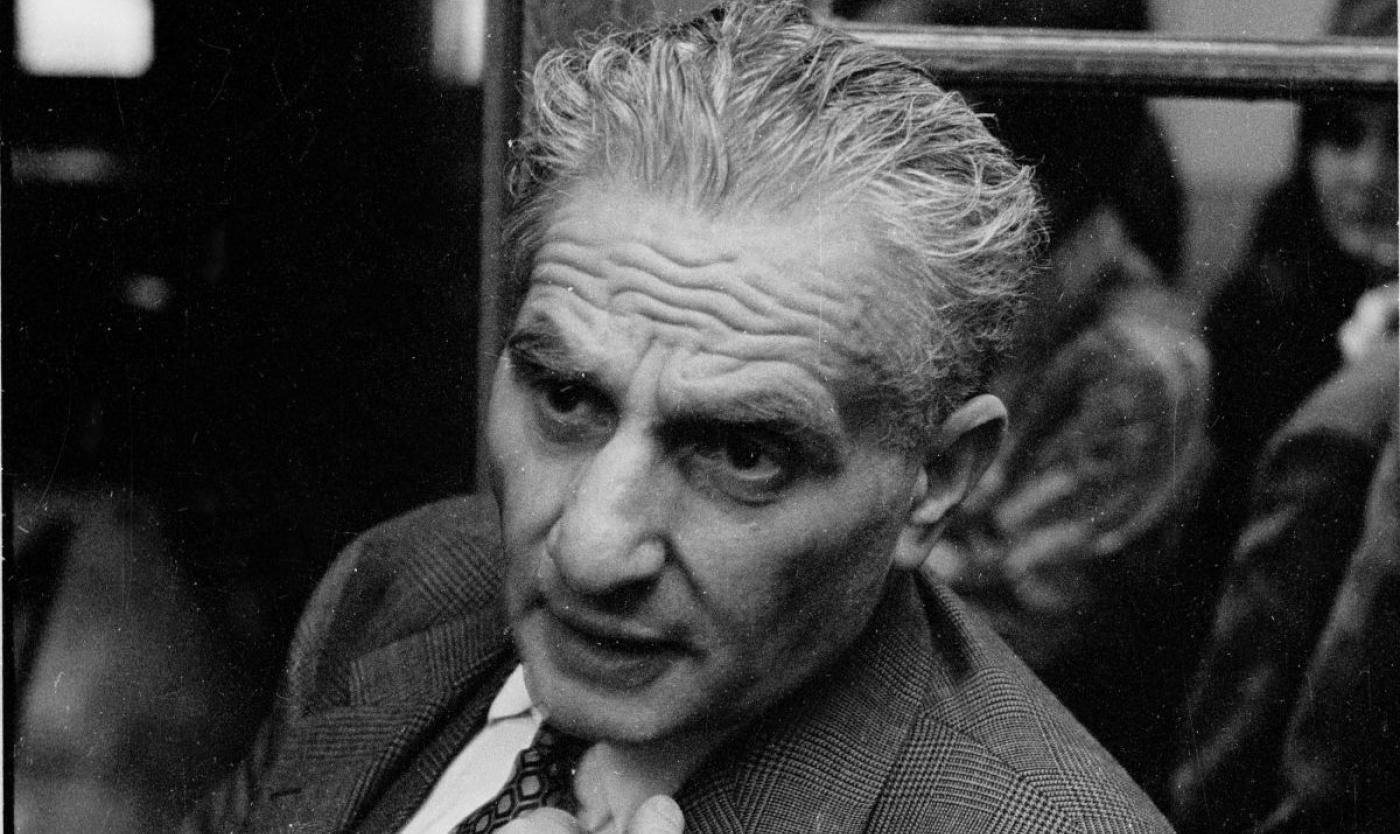

It is a continuation of decades of neglectful treatment of the resistance. Ask anyone, “Name a Belgian from the resistance,” and often there is a deafening silence. The major collaborators—such as August Borms, Cyriel Verschaeve, and Staf De Clercq—not only ring a bell for people, but they are commemorated with plaques and state-maintained tombs. As recently as 2021, the Flemish Parliament gave Borms and De Clercq a place in an honorary gallery of great Flemings.

This is the situation in 2024: we honor the criminals, but those who resisted a criminal regime are forgotten. This continues to deeply affect many families to this day. Almost daily, our association hears how children and grandchildren struggle with unresolved war traumas. Talking about resistance fighters is not discussing medieval, cardboard-cutout figures: it was barely two or three generations ago. These are local stories encompassing the full emotional spectrum: courage, betrayal, revenge, self-sacrifice, regret, love. Lives lived on the edge that, in every involved country, inspire films, series, publications, and theater productions. Every European country has a well-visited national resistance museum and incorporates the inspiring figures from its own history into education. At best, they make us reflect on our own choices in times of danger. And here? None of this exists.

The fuss over the so-called mythologization recalls the sour reactions of some academics to Bart Van Loo (Burgundians) and Tom Waes (The Story of Flanders). We warmly invite Roden and Vrints to one of our many activities so they can see with their own eyes that the academic world can work hand in hand with accessible, grassroots initiatives. Both can inspire, critically challenge, and strengthen each other. Fortunately, there are academic institutions that do believe in the power of citizen science. We are very grateful that the VUB embraced our call for more scholarly research. Last June, we presented our joint academic chair, “Traces of the Resistance,” at Brussels City Hall, in collaboration with historian Prof. Dr. Nel de Mûelenaere (VUB).

So what myth-making is there? After the war, the resistance itself was submerged by internal disputes and ideological debates—now we must avoid that risk. The only real myth created by Dimitri Roden and Antoon Vrints’ opinion piece is the notion that the association Helden van het verzet (Heroes of the Resistance) is creating a myth.

Discover the VUB Chair “Traces of the Resistance”