MOBI is one of the flagship research groups at VUB. Here, 125 scientists from dozens of nationalities are shaping the future of the electric car. “We founded MOBI almost twenty years ago,” says founder and director Professor Joeri Van Mierlo. “At the time, China was nowhere. Now they’re overtaking the Western car industry left and right. It’s high time we shift up a gear.”

“If I have seen further, it is by standing on the shoulders of giants,” Isaac Newton once said. For MOBI, that giant was Professor Gaston Maggetto. Joeri Van Mierlo calls him a visionary. “The early seventies were marked by the first oil crisis and a growing environmental awareness. Gaston Maggetto was among the first to see the potential of electricity in transport. He decided to conduct research into electrically powered vehicles. People laughed at the idea for a long time, but time has proved him right. He gained international recognition.”

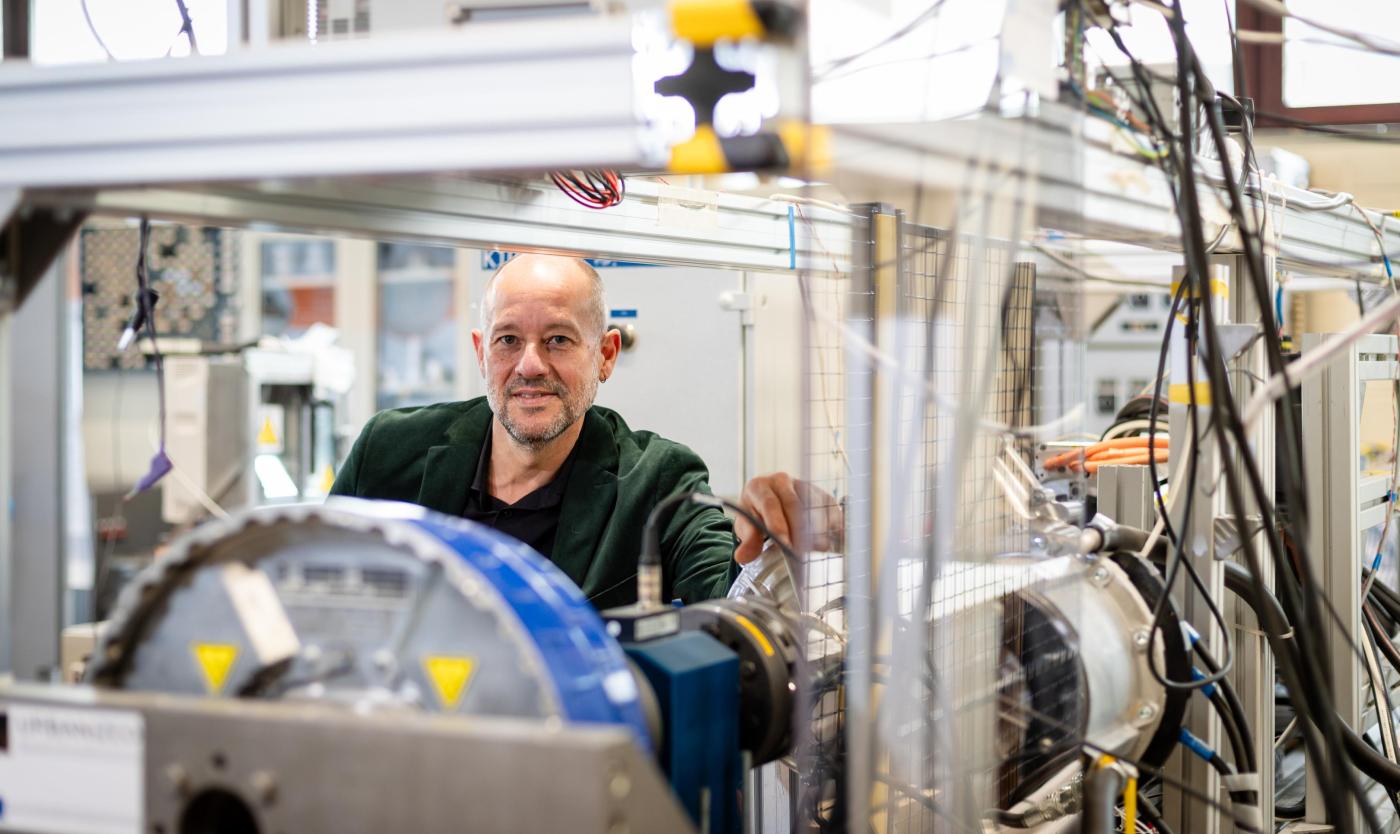

Joeri Van Mierlo

Nearly twenty years ago, Joeri Van Mierlo helped lay the foundation of MOBI, building it into an interdisciplinary research group. “Our engineers, for example, work alongside economists who calculate the total cost of ownership of electric cars – all costs over the vehicle’s lifetime. We also conduct life-cycle analyses to map the full environmental impact of every material, from mining to recycling. And we study consumer behaviour, because we want to understand how people react to new technologies like self-driving cars.”

Joeri Van Mierlo has since become a giant himself for the next generation. MOBI has grown into Europe’s largest research centre and reference point for electric vehicle research. For Joeri, it is a childhood dream come true – with a little help from coincidence. “I studied and earned my PhD at VUB, and in between I also did my civilian service here. Two weeks later, compulsory service was abolished. Honestly, I never regretted it. I was fascinated by mobility, and one of my tasks during civilian service was to design a traffic safety plan for the campus. Hard to imagine now, but at the time there were no traffic lights or cycle paths on the busy roads around campus. There were regular accidents.”

That is how Joeri naturally rolled into the mobility theme. From the beginning, his main motivation was the fight against air pollution and climate change. For him, the electric car would play a central role. “Walking, cycling or public transport is always better, but a large share of journeys will continue to be by car. Just reducing car use from 70 to 60 percent already requires doubling public transport. We can’t do without cars anymore. Then they should at least be as environmentally friendly as possible. Electric, in other words.”

It is only in recent years that the electric car has truly broken through. The road to this point was long and frustrating, mainly because of the composition of the batteries. Half a century ago – when Elon Musk was still in nappies – nine striking blue electric cars were already driving around the VUB campus: heavy Italian models with welded steel bodies, used by staff and students to commute between the Etterbeek campus and the Jette hospital. Even in car-sharing, VUB was ahead of its time.

“They ran on lead batteries,” says Joeri Van Mierlo. “Their range was at most 40 kilometres. And as a driver, you needed strong muscles, because there was no power steering or brake assist. You had to slam the brake pedal with full force and hope you stopped in time.” (laughs)

Those iconic blue cars would have deserved a place in a museum. Sadly, they rusted away completely over the years. The research went on, though. In the 1990s, lead batteries were replaced by nickel-cadmium. To promote electric mobility, Joeri Van Mierlo drove from Brussels to Monaco in those years, in a caravan that also included colleagues Gaston Maggetto and Peter Van den Bossche. They regularly stopped to give demonstrations at town halls along the way. They had plenty of opportunity, since the range of nickel-cadmium batteries was still only 70 kilometres.

“The holy grail of the sector: making batteries lighter, smaller and more compact – while still performing just as well”

Joeri Van Mierlo: “The difference compared to today is enormous. Not long ago, I made a similar trip again – driving electrically back and forth to the Electric Vehicle Symposium in Sweden. I had mapped out in several apps which stages I would drive and where I would recharge along the way. But that turned out not to be necessary: driving 500 km without stopping is already a challenge for the bladder and for fatigue. In recent years, there has been more than enough charging infrastructure added to avoid any problems.”

The big leap forward came with the introduction of the lithium battery. Although there is no such thing as the lithium battery. Lithium is always combined with other materials. By adjusting the amounts and ratios of those materials, significant improvements can still be achieved in many areas. Faster charging times, for example. How does Joeri view the recent stunt by Chinese manufacturer BYD: a battery that charges in just five minutes?

Joeri Van Mierlo: “Those five minutes don’t say much in themselves. Charging time is only one criterion. I immediately ask: is the battery affordable? How much energy can it store? How heavy is it? How big? How many times can it be charged and discharged? Is it safe? All those parameters matter.”

In the Electromobility Lab in Building Z, MOBI already has everything needed to study these parameters. The building itself is a maze and shows its age, but every corner is packed with sophisticated, gleaming equipment. A recent acquisition is a device that can test 300 different battery cells simultaneously. They also recently invested in a so-called dry room, essential for building prototypes of new battery cells.

Joeri Van Mierlo: “With MOBI’s battery team, we are now strongly focusing on developing solid-state batteries. At present, there is liquid electrolyte between the anode and cathode of a battery. We want to replace it with a solid material. Expectations are high, because such a solid-state battery could be made more compact and lighter. That is the holy grail in the sector: batteries that are smaller, lighter and still work just as well, so we can also make the vehicles themselves smaller and lighter. Our EPowers colleagues, also within MOBI, are doing the same for power electronics – the components that transfer electricity from the battery to the motor and enable speed, acceleration and so on. That team recently opened a new lab to conduct lifetime tests on those components.”

“We are developing systems to charge and discharge smartly – at exactly the right moment”

For this type of research, MOBI joins forces with other top European research groups in countries such as the Netherlands, Germany and Sweden. These consortia apply for financial support through European framework programmes and work closely with European car manufacturers. The ambitions are steep, the economic stakes enormous: Europe wants to hold its ground against the tidal wave of Chinese electric vehicles and – who knows – perhaps even regain the lead. “Twenty years ago, when MOBI started, China was nowhere. Back then, Japan and Korea set the tone. Things can change quickly. That should inspire us, and ideally push us to accelerate. The solid-state battery could be a decisive step. Though of course, our Chinese colleagues are not standing still either.”

MOBI’s perspective goes beyond the car itself. Research is also being conducted into the integration of vehicles into the electricity grid.

Joeri Van Mierlo: “We need to move towards a climate-neutral society, with a lot of solar and wind energy. But those are not always available. The electricity generated when the sun shines or the wind blows must be stored. You can store it in large stationary batteries, but electric cars offer an additional option. All those car batteries together have enormous storage capacity. When there is a surplus of electricity, hundreds of thousands of parked cars could store it and later feed it back – to households, to businesses, or to the grid. Together, they form one giant battery. That requires bidirectional charging systems between car and home, so that energy can flow back and forth as needed. We are developing systems to charge and discharge smartly – at exactly the right moment.”

Speaking of smart: in Willy Van Der Meeren’s iconic yellow buildings, MOBI researchers are also working on smart lighting for self-driving cars. “They are developing technologies that allow car lights to transmit communication signals to other vehicles – for example, to indicate that there are roadworks 500 metres ahead or that a car has broken down. With Waze, drivers still have to enter that information themselves. Self-driving cars will be able to do it automatically, without human intervention.”

A peek inside the labs of VUB scientists?

Join us on 23 September 2025 for the Academic Opening and explore the renewed VUB laboratories

On 23 September, VUB will not only open the new academic year but also the doors of its laboratories. Discover live the technological innovations and scientific breakthroughs our researchers are working on – the very ones that could soon make the headlines.