On 8 May it is V-Day, and this year also the 80th anniversary of the end of the Second World War. VUB will pay tribute to the resistance on that day, and will add 19 new resistance heroes to the Resistance Path. Reine Borms is one of them. We spoke with her daughter, Anne Duchaine, about her importance as a resistance fighter, her role as a mother, but also her life path and choices. “I didn’t have an average mother. No idea when it began to dawn on me that she had done very special things and that something very terrible had happened to her.”

Herdenk op 8 mei samen met VUB Belgische verzetshelden

How special is the 8th of May for you?

Anne Duchaine: “It is a very important day for me. Unfortunately, it has been swept a bit under the carpet, it is certainly not a ‘celebration’ day. My family – my mum, my dad, but also my aunt Christine Duchaine – were in the resistance. For them, that day meant the end of a heavy calvary.”

That day your mother is added to the Resistance Path as a resistance hero, you will speak in her name.

“That is of course also very special. My parents and aunt have passed away, what remains are photos and testimonies. That my mother is now being added to the Resistance Path is a great honour. I think everyone who gets a place there has fully earned it and also deserves not to be forgotten. Because honestly, I’m shocked at how quickly the Second World War has ended up in oblivion for many people. Yet at the time a heavy price was paid in the fight against Nazism and their far-right ideologies, which we see resurfacing more and more today. That’s why it’s very important to stay alert, so that we don’t fall into the same trap as in the 1930s.”

“My mother survived several concentration camps and also the death march to Sachsenhausen”

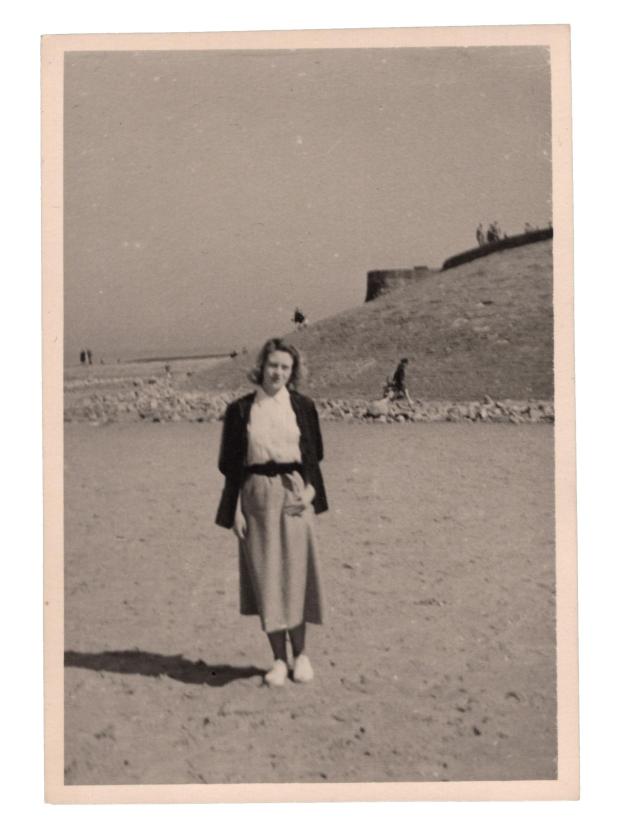

Daughter Anne Duchaine with mother Reine Borms

Does that frighten you?

“Yes. Only, history rarely repeats itself as some kind of duplicate. The far right today appears much more ‘civilised’ than the Nazism of the 1930s. They wear a tie, they watch what they say, they manipulate, but behind that is a growing provocation that will increasingly trigger social conflicts. They will increasingly feed the anger of the citizens, set them against each other: people with a migration background against ‘real Belgians’, Flemings against Walloons... The solution certainly doesn’t lie with the far right, the solution lies in solidarity measures. Today Trump is talking about the deportation of foreigners: we must be aware of that kind of language and pay attention to it. Olivier Mannoni, the translator of ‘Mein Kampf’ into French, once said: words are the harbingers of death. If there is talk of deportation, if children are separated from their parents, if people are regarded as inferior and don’t get the protection they deserve, then you are already very close to the scenario under Nazism.”

How did your mother’s story live on within the family? Was it talked about a lot?

"My mother survived the concentration camps of Ravensbrück and Berlin, and also the death march to Sachsenhausen. She returned as a very, very ill woman—both physically and mentally. As a child, I often went with her to the doctor, a physiotherapist came to the house, and sometimes my mother was in a bad mood because of the pain. I realised early on that I didn’t have an average mother. I have no idea when it began to dawn on me that she had done very extraordinary things and that something terrible had happened to her. I was probably very young—a child picks up more than adults realise. It was only much later that I began to understand what the implications were. My mother herself didn’t really feel the need to talk much about it, and I didn’t feel much inclined to ask. Perhaps because I secretly hoped for a more carefree childhood.”

What impact did it have on you, as a child and now as a woman?

“My mother and I were very different personalities to begin with. The family she grew up in fell into poverty after the stock market crash of 1929. My mother received a scholarship to study and was extremely intelligent. She was a perfectionist, both in her studies and in her fight against social injustice. I myself grew up with a father who was a doctor, in a culturally privileged household—something my mother never knew. But of course I inherited traits from her, like not letting yourself be pushed around, not simply accepting the dominant discourse, not allowing your freedom of thought to be compromised.”

“My mother would have been frightened by all the current measures that are putting social achievements under pressure”

What kind of woman was your mother?

“Her father fled from Sint-Niklaas to Brussels to avoid being associated with August Borms, my great-uncle and a collaborator in both wars. My grandfather lost all his money in the stock market crash. From the age of fourteen, my mother gave private lessons to help support her parents financially. As I said before, she was very intelligent. But she could also be extremely tough, which undoubtedly helped her during the resistance, but which, for me as her daughter, was sometimes more difficult. She certainly wasn’t the cuddly type. That doesn’t take away from the fact that I have a great deal of respect for my mother—for her perseverance, her strength, and also for the clarity with which she was able to analyse the world right up to the end of her life.”

How did the family live with such a loaded family history—the schism between resistance (Reine Borms) and collaboration (August Borms)? Did it leave deep wounds, and have they since healed?

“I’m French-speaking and from Brussels. If my mother hadn’t moved away from Sint-Niklaas back then, I might still be living there and be a Fleming. In that sense, I’m the embodiment of the family schism. August Borms was executed in 1946. In fact, it was my grandfather who suffered the most under the name ‘Borms’. It was only when I started studying in Brussels and mentioned my mother’s surname, ‘Borms’, that it stirred up some commotion—and that’s when I began asking my mother questions about it. She was intelligent enough not to burden me with hatred towards that man. In any case, I find it very courageous of the VUB to have added my mother to the Resistance Path, despite her surname being Borms, and I want to explicitly thank them for that.”

What would your mother stand up for in these turbulent times? Who would she defend?

“She would certainly oppose anything linked to religious obscurantism, scientific obscurantism, censorship... I think she would have remained loyal to her socialist and communist friends. She would have been very frightened by all the measures currently putting social achievements under pressure—achievements that took great effort to win after the war. She would have shown solidarity with the victims of social inequality. That was always a very important issue for her.”

What life lessons did you learn from your mother?

“The negative is that I’m afraid of the far right and its influence on our bodies and minds—afraid of what could happen, of Von der Leyen calling on Europeans to buy more weapons and even to go to war. The positive is that I remain loyal to all those who persevere in their personal quest and in their search for truth, knowing that an extreme truth does not exist.”

Reine Borms 'sur la plage'

Anne Duchaine

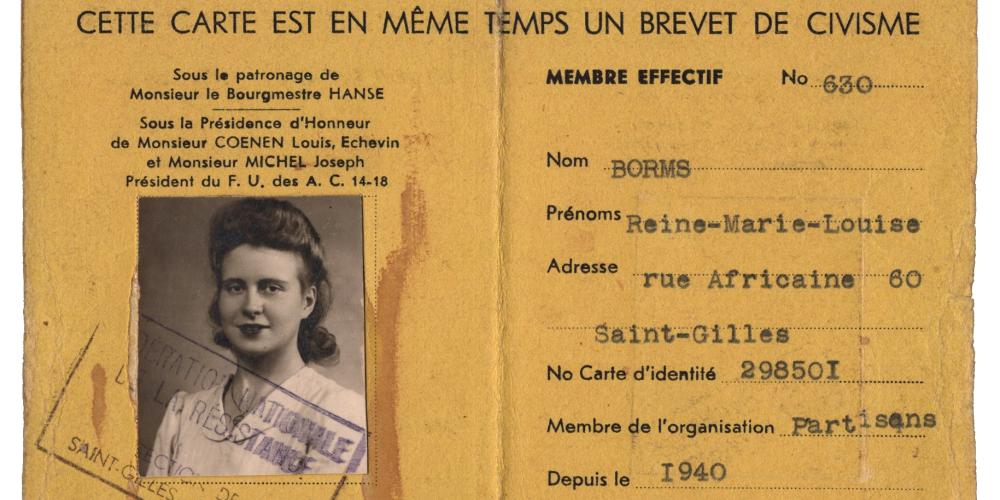

ID

Anne Duchaine, daughter of Reine Borms and Jacques Duchaine. Author of Borms, une famille entre collaboration et Résistance, published by Racine.

Reine Borms

(1923–1999)

As a student, Reine Borms joined the communist resistance, working as a courier, editor, and intermediary for comrades sentenced to death. She survived several Nazi camps, but the physical and psychological scars of her resistance marked her for life.

*This is a machine translation. We apologise for any inaccuracies.

Chair Traces of the Resistance

The VUB Chair Traces of the Resistance is a collaboration between the non-profit Heroes of the Resistance, VUB Research, and the Faculty of Arts and Philosophy. This chair aims to respond to the growing societal need to reinvigorate the memory of the Belgian resistance against the Nazi occupiers.