In the Vaudeville theatre, in the heart of Brussels, the Vrije Universiteit Brussel will award four honorary doctorates on Friday, June 6. The most well-known laureate is undoubtedly philosopher and bioethicist Peter Singer. From a humanist, atheist perspective, the Australian animal rights pioneer has been reflecting for over half a century on solutions to poverty, disease and other forms of suffering. Even if that means taking controversial positions. “People sometimes hold on to outdated ideas, often rooted in religious traditions. That’s dead weight we need to be able to debate.”

Book your free tickets for the Doctor Honoris Causa CeremonyBook your tickets for the lecture about animal rights by Peter Singer

Peter Singer was born in 1946 and grew up in a Jewish, non-religious family in Melbourne. His parents were Austrians who emigrated to Australia after the annexation by Nazi Germany. Three grandparents died in concentration camps, Singer says during a Zoom conversation. “One grandmother followed us to Australia – she died when I was nine years old. In Melbourne, my parents knew people who had survived the camps. I still remember a woman with a tattooed identification number on her arm. My parents didn’t hide those stories. They explained them to us, in a way children could understand.”

You’ve devoted your life to ‘effective altruism’. That movement wants to reduce suffering, as effectively as possible and based on scientific evidence. Was that ambition the result of a sudden insight or a gradual evolution in your thinking?

Peter Singer: “Rather the latter. But there was a turning point. When I was 24, I became aware of the immense suffering in intensive livestock farming. I realised that, as a meat-eater, I was complicit in it. At the time, few people were concerned with that issue, let alone trying to change it. I thought: maybe I can play a role here.”

Were your parents concerned with animal rights?

“Not really, or at least not in depth. When I walked along the beach with my father, he would sometimes point out the fishermen throwing caught fish straight into a basket. He didn’t understand how people could find that a pleasant afternoon, sitting there while those animals gasped for oxygen next to them. That might have planted a seed…”

"Especially European legislation has meant a lot for animal welfare. Elsewhere in the world, animal suffering is much worse"

You’ve been a vegetarian since you were 24.

“Yes. I also try to live vegan and avoid animal suffering as much as possible. It’s a small effort to buy free-range eggs.”

In principle, you don’t object to meat if the animal has led a dignified life and is slaughtered without suffering?

“Perhaps not in principle, but in practice, on a commercial scale, it’s very difficult to ensure that this is the case. Shellfish, like mussels and oysters, are probably not a problem. They likely don’t experience conscious pain.”

Then I have a good tip for when you come to collect your honorary doctorate: moules-frites is a Belgian classic.

“Is that so? Okay.” (laughs)

Your book Animal Liberation, published in 1975, became an influential bestseller. Is animal welfare the topic in which you’ve had the most impact?

“Probably, also because there are so many industrially farmed animals. Every improvement positively affects the lives of millions of animals.”

Half a century has passed. Are you pleased with the progress made or rather disappointed?

“More could have happened, but fortunately a lot has changed. Especially European legislation has meant a lot for animal welfare. The EU has banned battery cages and small individual pens for pigs and cows. These are meaningful reforms that prevent some of the worst suffering. And they will become more important still if, as has recently been proposed, the EU requires other countries wishing to export to the EU to adopt those standards, not only for slaughter, as the current rules require, but for the way animals are raised too. On the other hand, there’s still a lot of animal suffering. In China, the market has grown enormously, and there it’s almost entirely industrial farming.”

"If you stop initiatives like USAID, you know for certain that people are going to die. That is heartless"

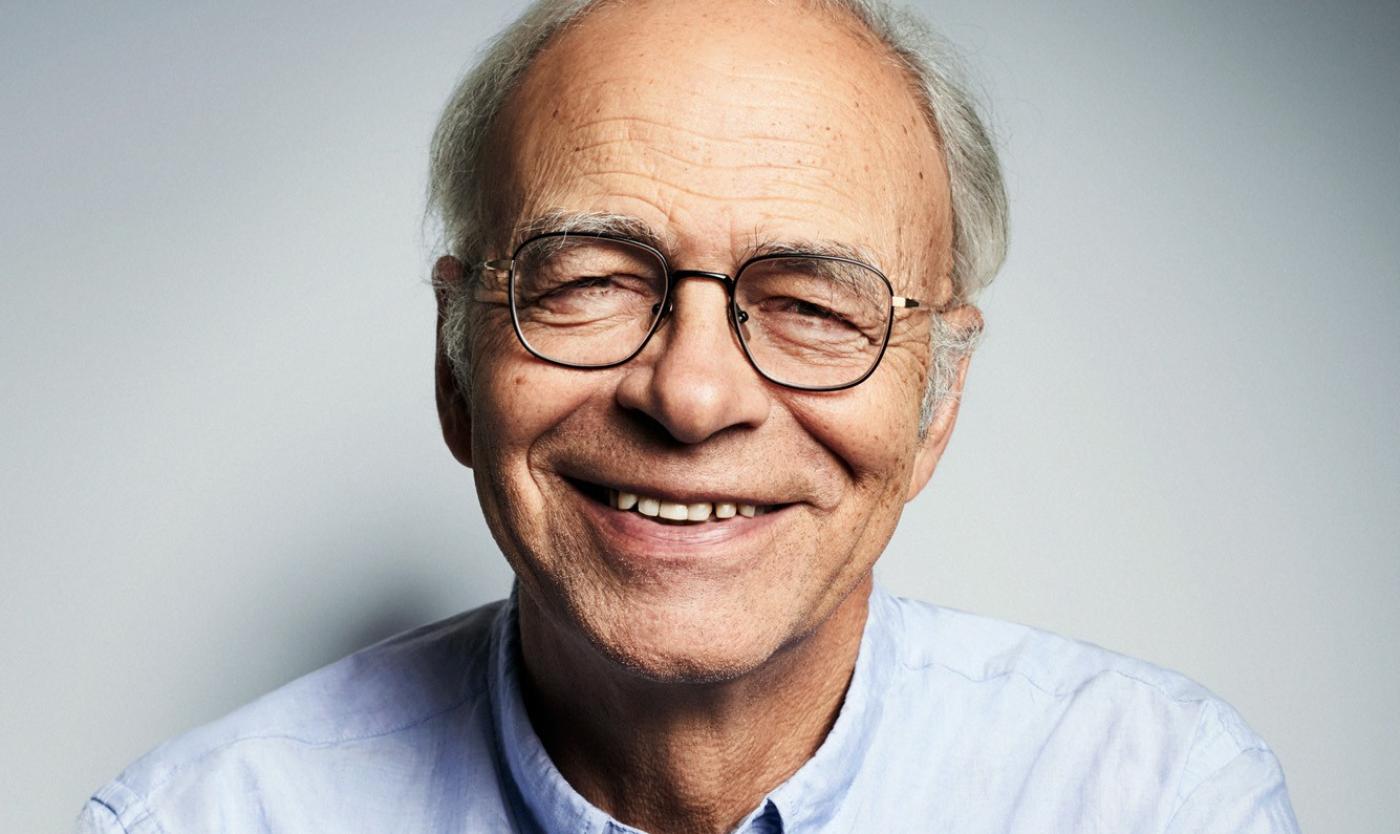

Peter Singer (c) Alletta Vaandering

You’ve also advocated for human welfare.

“My article Famine, Affluence and Morality came out a few years before Animal Liberation. The message was that people who can afford to spend money on luxuries have a moral obligation to help people in poor countries. I further developed that idea in the book The Life You Can Save. That’s also the name of a non-profit organisation that fights extreme poverty and disease worldwide. It helps donors find the most effective charities so that their contributions have the greatest possible impact.”

You often say it doesn’t have to cost a fortune. Free vaccination programmes save many lives, just like mosquito nets against malaria.

“Absolutely. And they don’t cost more than what people in wealthy countries spend on a vacation.”

What’s your view on the dismantling of the American development agency USAID?

“Absolutely horrendous. Look, I think it’s very reasonable – and also in the spirit of effective altruism – to ensure that the programmes we fund work as effectively as possible. But to simply shut everything down is truly heartless. USAID funds antiretroviral medication for people with HIV in Sub-Saharan Africa. If you stop that, people will die – that’s a certainty. You can screen programmes without freezing everything. It’s either unbelievably thoughtless, unbelievably callous, or a combination of both.”

"People often find things controversial because they cling to ideas that may have been appropriate in the past, but no longer apply"

Doing good is no longer in fashion, not just in the US. Issues like poverty, climate, animal welfare or war violence seem to be snowed under everywhere. Selfishness is growing. Is this the end of altruism?

“I think the pendulum will swing back again. I hope so, anyway. I can’t believe people are so bad that they’ll simply ignore what’s happening in other countries. Climate change, at any rate, will be felt everywhere – also in rich countries. Everyone loses if we don’t take that problem seriously.”

Some forms of suffering can’t be solved with a mosquito net. You don’t shy away from launching controversial solutions. For example, you consider euthanasia for newborns with severe, incurable disabilities morally defensible if these disabilities lead to unbearable suffering without any prospects.

“People often find things controversial because they cling to ideas that may have made sense in the past but are no longer valid – for example, due to new technological solutions. Or resistance arises under the influence of religious traditions, even though in many countries, a growing majority of people say they’re not religious. That creates dead weight that we must be able to debate.”

Such debate can become tumultuous. Once, during a lecture, your glasses were broken.

“That was in Zurich. Someone was so angry that he ripped my glasses off, threw them to the ground, and stomped on them. So the lecture didn’t happen. A pity, because I’d have liked to discuss the issue with several people in wheelchairs sitting at the front. They wanted to explain to me why I was wrong, and I would have liked to hear their views. They strongly disapproved of that person’s behaviour, by the way.”

You believe freedom of expression and free debate are under fire in academic circles. That’s why in 2021 you co-founded the Journal of Controversial Ideas with two other scholars. What is the aim?

“It’s an open-access peer-reviewed academic journal, willing to publish articles with controversial ideas – a safe space that can’t be cancelled. Articles may be published under a pseudonym if authors are concerned about repercussions for their careers or safety. Almost one in four authors uses that option.”

There are a striking number of articles about gender, race and identity in the Journal of Controversial Ideas.

“I can’t deny that. We receive many article proposals on those topics.”

Black Pete, the n-word, trans women in women’s spaces, the personal responsibility of people with obesity… It’s an ethical hornet’s nest.

“If an article passes our peer-review system, we publish it. That doesn’t mean we agree with it – only that it’s sufficiently well-argued by academic standards to be published.”

One article is about the transition of trans minors. The authors argue that gender-affirming care insufficiently considers the medical risks, the unpredictable outcomes and the irreversible consequences of treatment.

“That article is from 2022 and was ahead of its time. The message was that, especially regarding minors, we may have gone too far, too fast. Recently, the British government banned puberty-blocking hormone treatments for minors, by the way.”

"Giving in to the demands of the American administration would go against academic freedom and independence, and a whole range of other important academic values"

Have you published articles you personally thought: isn’t this going too far?

“Last October, we published an article comparing the intelligence of migrants in Germany to that of native Germans. Very controversial and delicate. Cultural and language barriers, for example, can influence test results. Moreover, such an article risks reinforcing existing racist prejudices. We sent it to several reviewers, who read it carefully and asked for revisions, which the authors made. Eventually we published it, along with a commentary piece that was very critical of the article itself and of our decision to publish it. The original authors’ reply is currently undergoing peer review again.”

The Journal of Controversial Ideas seems mainly a response to cancel culture from progressive voices. Yet now it’s the right wing that’s stomping through academia in the US. You’ve worked at Princeton University for 25 years. How do you view the clash between the Trump administration and universities?

“I’m proud that Princeton is resisting the new administration’s demands. Christopher Eisgruber, the president of the board, was a colleague of mine at the University Center for Human Values. He made his position very clear: giving in to those demands would go against academic freedom and independence, and a whole set of other important academic values.”

"One thing is certain: a tidal wave of lawsuits is coming"

But Princeton risks losing $210 million in federal research funds.

“Then so be it, is their view. That’s the right attitude, I think. Harvard took the same approach, and even Columbia now seems unwilling to give in to everything. Hopefully, this gives other universities the courage to resist too. One thing is certain: a flood of lawsuits is coming. We’ll have to see whether the Supreme Court upholds the law or takes sides politically.”

You’re receiving the honorary doctorate from VUB also for your outspoken views on abortion and euthanasia. Euthanasia has only recently become possible in about six Australian states.

“Here it’s not called euthanasia, but VAD – Voluntary Assisted Dying. In Belgium, a doctor administers the lethal substance. In Australia, you have to take it orally yourself. Only if you can’t do that anymore may a doctor take over.”

In Belgium, there is a push to expand the law to allow people with advanced dementia to receive euthanasia based on a living will.

“A good idea. At the moment, people have to give up months or years of acceptable quality of life not to miss their chance. My mother had dementia. In the last two years, she no longer knew what was happening around her and didn’t recognise my sister or me. She would have hated living like that. But she had no choice.”

Will you stay in Belgium a little longer after receiving your honorary doctorate?

“I’m quickly travelling on to Amsterdam. There, together with The School for Moral Ambition (an initiative by the historian and author Rutger Bregman, ed.), we’re organising the very first conference on profit-for-good companies: businesses that donate all or a large portion of their profits to charity. Another great example of effective altruism.”

Book your free tickets for the Doctor Honoris Causa CeremonyBook your tickets for the lecture about animal rights by Peter Singer