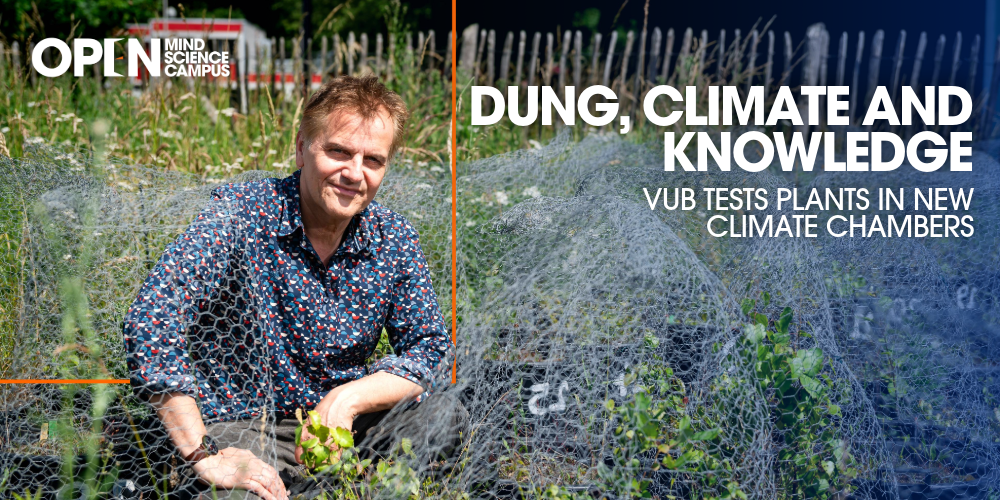

For years, Harry olde Venterink has combined fieldwork in African and Brazilian savannas with experimental plant research in the greenhouses and test gardens on the VUB campus. Soon, six new climate chambers will be added, on the fifth floor of Building F. “We can study plants under very specific conditions, by adjusting light, temperature, humidity, and CO₂ concentration.”

When plants or animals die, they feed the soil. New plants and animals then live and grow, until they too die. Nature runs in a cycle of birth, life, death, and rebirth. If you grew up with The Lion King, you learnt this lesson with Simba.

This Disney wisdom is not far from science. The same cycle is central to the research of VUB professor Harry olde Venterink from the WILD research group (Wildness, Biodiversity and Ecosystems under Change). He studies the interactions between threatened native and invasive exotic plant species, as well as between plants, herbivores, and the dung those herbivores produce. The focus often lies on the balance between nitrogen and phosphorus in the soil – a key factor in ecosystems. Harry explains with an example from the African savanna.

Harry olde Venterink: “Giraffes eat the leaves of the acacia tree. The acacia is a nitrogen-fixing plant: it pulls nitrogen from the air and is therefore nitrogen-rich. As a result, giraffe dung is also rich in nitrogen. This dung stimulates plants that need a lot of nitrogen to grow but aren’t nitrogen-rich themselves, such as grasses. Those grasses are then eaten by zebras. Zebra dung is low in nitrogen, which stimulates the growth of nitrogen-fixing plants like acacia. And so, the circle closes. This closed system keeps the savanna stable.”

“Where large herbivores graze, clover takes over”

Hypotheses from this kind of fieldwork are confirmed in the greenhouses of the research group. These stand on the roof of Building E – you can see them glinting in the sun from the ground – and are currently being renovated (see box).

Harry olde Venterink: “We collect plants and dung in Africa or Brazil and bring them back to campus. We grow the plants in the greenhouse, combined with different types of dung. This research confirmed our hypothesis: zebra dung does indeed promote nitrogen-fixing plants such as acacia, while giraffe dung mainly encourages grasses.” In the greenhouse, Harry has already carried out a lot of research into the interaction between plants and herbivores, from the small rabbit to the huge bison. More specifically, he looked at the effect of dung quality on competition between plant species.

Harry olde Venterink: “We found that rabbit droppings are the most favourable for achieving a high diversity of vegetation. That’s because the nitrogen-phosphorus ratio in rabbit pellets is well balanced. The dung of large grazers – think cows, horses and bison – contains relatively little nitrogen. That stimulates the growth of plants that can fix nitrogen from the air – think of the acacias in Africa. Here, it’s more likely to be species such as clover. That’s why clover comes to dominate and plant diversity decreases in places where many large herbivores graze.”

The researchers also repeated the greenhouse experiment outside in their test garden, a patch of land between Buildings G and I. There, the same mix of plant species grows in large pots, combined with rabbit, horse and bison dung in different concentrations. Unexpectedly, clover in the pots with nitrogen-poor dung from large grazers dominated less strongly than in the greenhouse.

Harry olde Venterink: “The effect of dung works out differently outdoors than under glass. The main difference is temperature. In the greenhouse it stays more constant, outside it varies greatly. Temperature influences symbiotic nitrogen fixation in plants, and with it the effect of dung from different large grazers on vegetation composition. These are the kind of variables you want to include when you think about future scenarios for a warming world, or when comparing a city with its heat islands to the cooler countryside.”

“We share the climate chambers with other research groups”

To study these phenomena further, you really need a climate chamber. This is a sealed, controlled plant growth room in which light, temperature, humidity and CO₂ concentration are regulated precisely. Researchers can use them to test how different plants react to warm, cold, wet or dry conditions. Or to simulate, through different scenarios, which plant species will withstand the higher temperatures and CO₂ concentrations of climate change.

Harry olde Venterink: “Climate chambers have been on our wish list for a long time. Because we share this facility with all the research groups in Biology, we can now install six at once. This means we can study in a single experiment how plants respond when you raise the temperature step by step, say from 15°C in the first chamber to 25°C in the sixth. By sharing, much more becomes possible!”

Blueberries and invasive exotics

The greenhouse on the roof of Building E is the playground of professor Harry olde Venterink and his fellow researchers of the WILD group. They share this research facility with professors Geert Angenon and Joske Ruytinx and other researchers from the Plant Genetics and Microbiology groups. The greenhouse is currently being upgraded, to make temperature and ventilation more controllable. During our visit we encountered a colourful mix of ongoing experiments.

Harry olde Venterink: “In those pots we add invasive exotics – in this case grasses from southern Europe – to low-, medium- and high-productive native plant species, such as sorrel and various grasses. We suspect that these exotics don’t just dominate native plants because of climate disruption or their own characteristics, but that this mainly depends on other environmental changes such as increased nitrogen availability.”

The other experiments look just as intriguing. One investigates the impact of different antibiotic levels on plant growth, another examines whether butterfly larvae thrive equally well on native blackthorn as on related invasive species, and yet another looks at the impact of micro-organisms on the plant–soil interaction. Even the tasty blueberry is under the microscope.

Harry olde Venterink: “Cultivated blueberries struggle to absorb iron. Frederik Van den Eeckhout, a WILD researcher with colleague Franky Bossuyt, is studying whether the plants take up more iron if they are grown together with grasses. Grasses are better at releasing iron from the soil than many other plants. We are testing twenty grass species. The hope is that they will help the blueberries absorb iron. We are learning a lot here from processes in the ‘wild’, hoping to use that knowledge for more sustainable farming.”